Olle Svenson |

|

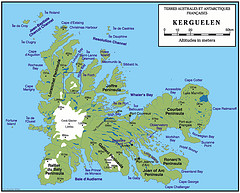

Now I will try to write about a trip I made to the island Kerguelen a long time ago. Kerguelen is an island in the South Indian Ocean. It is situated around 70 degree east and 50 degree south. At this time the island was not populated. I read some time ago that Australia had established some military bases or stations on the island during or under the Second World War, so now you may find some living creatures except from seals, penguins and birds.

The first time I heard about Kerguelen was on the 21 of May 1920. I was working in Tnsberg in Norway at the time. At dinnertime one day one of my friends asked me if I would like to go to Krugeluren and hunt seals. Sure, I said, but what is Krugerulen. I dont know he said but I think it is an island somewhere. When we had finished eating we went to the Naval Office and asked for signing for a job going to Krugerulen for seal hunting. There is no such place said the clerk but for Kerguelen we need people. Ok, we said, because if the name was Kerguelen or something else did not matter at all. We had to sign a contract, that I still have, and after midsummer we should get further order and be ready to leave with short notice, the clerk said.

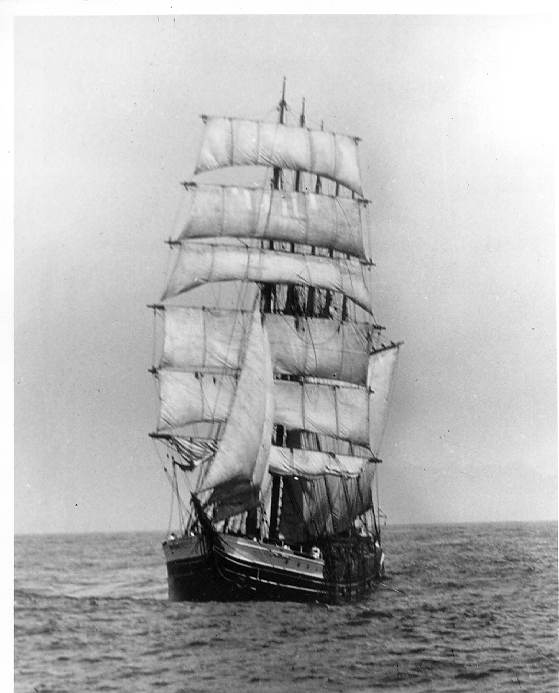

On July 7 we got orders to go to Kristiania, (Oslo) there we entered a passenger ship named Kalypso, as I recall it. The ship went to Hull in roughly 40 hours. In Hull we went directly to a train station and took a train to Newcastle on Tyne. From there we took a bus or a tram to North Shields and to a so called boarding house where we stayed a couple of days. The ship we should enter was not ready yet. Its name was S/S Plough. The next day we went to check the ship that should be our home for the coming year. We became a little astonished when we saw what Plough really was. She was a former fish trawler, 95 feet and could load 90 tons including bunker and all. So, you understand that the ship was not a huge one!

And we should go to Australia almost!

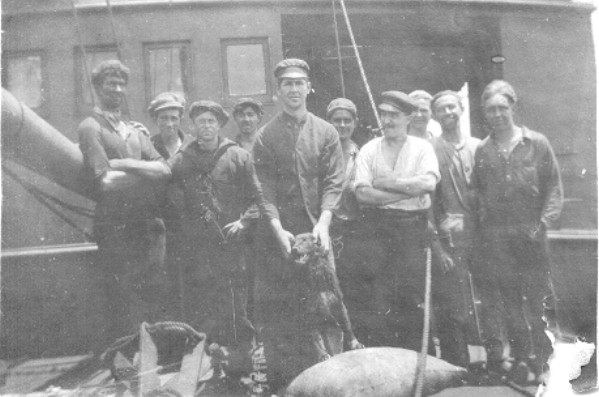

The new crew aboard the 'Plough' at North Shields Some days later we were told to go and sign the ship papers. When I was on turn the clerk asked me: Do you speak English? Yes, I said. Alright, he said, giving me a pen and pointing at a bunch of paper. I signed and what I signed was not clear to me until much later. Salary was 12 pounds and 10 shillings per month for a single trip to Cape Town, South Africa. In the evening next day our journey began.

The distance from England to Kerguelen is approx. 17.000 km compared with the distance from Liverpool to New York which is 5.600 km.

We had lovely weather both in the Channel and in the Biscaya Bay and one evening we anchored in the inner bay of Las Palmas. The next day we bunkered coal and food and already in the afternoon we were ready for take off. Even we, living in the stern, had bunkered tobacco, cigarettes, matches, fruit and other things necessary for living. Regarding the fruit we bought mainly bananas. We had one stock of bananas each hanging under a sun sail when we went to sea again. Each stock contained 150-200 bananas. We paid 10 shillings per stock which was 10 re, (0,10 SEK). In the beginning we could eat them as they became ripe but in the end we could not keep pace in spite of eating as much as we could.

Shortly after leaving Las Palmas we were in the Northeast Trade Wind. That is, as everyone knows, a wind blowing the same direction most of the year at a speed of 10-15 m/s. The Northeast Trade Wind has a corresponding wind on the other side of the doldrums called The Southeast Trade Wind. In the Trade Winds weather is nice almost all the time, warm and almost no difference between day and night so living is like being in a paradise. The Flying fishes started to occur in large amounts. They took of in front of the stern and sailed some 10 meters, then landing with a splash. In the evenings we hang a lantern at the front of the steering cabin and than we sat waiting. Suddenly we heard a sound from the deck. A sound that is very much like the one that our Swedish mackerels make when you have caught them and put them on the flooring. Flying fish taste very much like mackerel. The lantern was hung up because the fish fly towards the light and every one that landed on deck landed in the frying pot. The Big Dipper (Karlavagnen) sank more and more into the horizon to the north and finally disappeared totally.

But soon you could see at the south horizon another star group, the South Cross which is the special star group of the South hemisphere.

Passing the equator or The Line did not bring any change in our daily boring life. Probably all my crew mates had passed the line earlier so it was not much to bother about. I was the youngest onboard and also the youngest arriving to Kerguelen. When we passed the sun I made an experiment that our chief engineer had taught me. I placed an empty bier bottle on deck and when the sun was exactly above us I cold see the sun at the bottom of the bottle. There was no shadow so we were straight under the sun. As you know the sun is only over the equator at the vernal and autumn equinox. At other times it is on its way to or from. When we have winter it is south of the equator and in summer it is north of up to 22.5 degree.

Under the burning sun on the equator. Author Axel J. Svenson is on the right.

Time went and we passed the doldrums, the South East trade winds and after 44 or 45 days after leaving North Shields we headed into Table Bay and into the dock in Cape Town. The first part of the voyage was over, a trip of 11,000 km.

In Cape Town we had to sign off S/S Plough. We got an extra pay above the contracted amount and checked in at the English Seafarers Home for around three weeks. In the meantime two more ships arrived, also bound for Kerguelen. One was a sister ship to S/S Plough and was named Galaxy, the other was a tanker at 700-800 tons named Kildalkey. A fourth ship arrived later to the island. Its name was Kilfenara and was a sister ship to Kildalkey.

During the three weeks we stayed in Cape Town we got acquainted with the city quite well. We went everywhere, in the city itself as well as in the surroundings but not to the Table Mountain. I never went there not later either.

One day in the later part of September we left Cape Town for the last and most difficult part of the voyage. All three ships left at the same time and it was agreed that we should keep company all the way to Kerguelen. Weather was fine the first couple of days but after three days weather became worse and soon we had a heavy storm. We were in line with Cape Agulhas, which is the most south part of Africa, not Cape of Good Hope which people believe. The two smaller ship could not stay on course any longer but had to lay on the weather in order not to be broken down by the waves and the water. The second night Kildalkey disappeared and we did not see her until we reached the island. For how long time the storm lasted I do not know but it lasted so long time that we were completely worn out physically and mentally. To eat we had hard bread, canned food and water. The canned food, mainly meatballs, we ate directly from the container. In the long run it was terrible but we did not starve. To prepare hot food was not possible.

But, everything will come to an end, even this and in the morning of the 22nd day we spotted the fairly high, snow covered mountains of Kerguelen. It was a gloomy sight. The inner part of the island was covered by eternal snow, only at the coast line there was a strip of uncovered ground. Any tree could not be found on the entire island and not even potatoes could grow there. Before evening we were tied up at our head base named Jeanne dArc.

-- -- -- --

Kerguelen map------------------------Kerguelen Island------------------------Port Jeanne d'arc We were greeted by the Kildalkey crew and the boss of the base. He said: When we saw you coming through the straight a big stone fell from our chests. We were all convinced that we should not see you again. We thought that the ships had been broken down by the heavy storm and that you were gone forever.

Now we had a lot of work to do before we were ready for fishing and the first fishing day was October 25. Among other thing our boiler should be overhauled. In connection to this we had an accident that demanded one human life. When the boiler was reheated and pressure was almost at level a manhole packing blow and boiling, overheated water came out on the flooring. A man working in the area was struck by the water and scalded alive. Almost the whole body was burned. He died after an hour or so. We buried him on the island. His name was Steiner.

A new packing came into place and the boiler was heated again. This time the packing was not leaking. Fishing could not be stopped by such a small detail. During fishing/hunting one of the crew had to be watchman. We had a three weeks turn. The watchmans job, among others, was to care the boiler and to have full pressure before work in the morning. If the firemen should do this by themselves they should never had a chance to recover so this was an important work. I had to take the first shift after the accident. One of the first nights standing on the flooring loading coal I heard a sound, pssssss. I throw the shovel away and ran. One more time, I thought, better run away. Up on deck I close the door and stopped, listening for a couple of minutes. As nothing could be heard, I climbed down again, step by step, ready for take off again. When I came to the place where I had thrown the shovel I heard the sound again, but now I had calmed down a little and tried to localize the sound. It was not coming from the manhole cover but from the port side somewhere. After a further investigation I found a stuffing box of a valve leaking a little. At that time I learned what panic frightening was.

- - - - - - - -

All images of Port Jeanne d'arc - taken from Kevin 0'Rourke's website HERE You can say that our working hours were dictated by the sun, i.e. we started to work at sunrise and stopped at dawn. We did not work like this all days, but very often. Working week was 7 days. Days off were Christmas Day and New Years Day. Sundays did not exist so we did not have any lazy men work! It happened, coming down in our mess room after a working day, we took of the rain coat, fell into the bunk and fell a sleep momentarily. I had the anchor chain box and chain outlet a feet from my head, laying in my bunk and at several occasions when anchoring using 60 fathoms of chain I did not wake up if in sleep. That is not sleep that is unconsciousness! Bad weather days gave us a day off now and then, maybe two, but around Christmas, they were rare. On such a day we slept 24 hours in a row and sometimes even longer.

Bad weather, strong winds is a chapter for itself down there. These days came without warning and we could have full storm within 5 minutes. We had no instruments to read wind speed but for sure we had wind at 50 m/s. In 1932 in October living in Strmstad they measured 42 m/s. When I thought back on Kerguelen I said to myself: If it is blowing 42 m/s here, we must have had 60 m/s down there. This might be exaggerated but I am convinced that we had wind speeds above 50 m/s several times. The winds could last for two days, sometimes three and seldom four but they all stopped as fast as they started.

Early, before noon, on Christmas Day we arrived at the base, Jeanne drc with a full load of seal fat. We figured to celebrate Christmas after unloading the fat but no way.

Some of the crew aboard the Plough We were asked to speed up unloading and leave immediately. We had worked hard to have full load before Christmas and stay and celebrate Christmas with the crew at the base. We were all upset but that did not help. We went out at sea again but we did not go so far this time. Just around the corner of the first peninsula where we could not be spotted. There was an anchor area called Three Islands. We stopped and stayed over Christmas day but next day we went back to work. Our Captain came forward in the afternoon bringing some liquids, whiskey and rum. But, we had manufactured a distilling unit and for the purpose we had made some drank also. Everything got organized and put on the fireplace in the mess. Soon the drops started coming out of a pipe and a great tasting took place. We could lie in our bunks using lengthened table spoons to reach the dripping. When the spoon was full next spoon was in turn. During the evening there was a lot of talking, laughing, singing and even crying before one after the other fell asleep. Waking up the next morning the small bucket below the drip pipe was full of distilled material.

On Christmas Day we went ashore and shot some rabbits. There were plenty of rabbits on the island. On one of these islands there are a number of graves,15-20, on a graveyard. A great number of crosses were still there but we could not read any inscriptions. On board we had a description of the island and it said that the graves contained Americans from early 1800, probably killed by beriberi. They had been whale and seal hunters. Also we found a big pot of cast iron with a volume of 200 litres or more. It was plastered into a stone wall. It had probably been used to cook the fat.

Christmas of course meant some difference regarding food. We got rice porridge and meat from a pig newly killed at the base. Also we got white bread like Danish. They tasted very good with the coffee.

New Year became like Christmas but we did not hurry back to our base. Time ran with hard work, weather became colder, days shorter and the stormy days more often but with storm also lazy days. The snow border that during summer had moved away from the coast came back slowly. It was snowing or raining almost every day now. At Christmas time we could have days with only a few clouds and sunshine but a whole day of sunshine was not experienced during the 5 months we stayed in the area.

Time went by and one day we had March 25. The crew became beside themselves of excitement, the last fishing day! We spent a week or more to tidy up on deck, in cargo rooms, in the mess and in the engine room and on a beautiful day in early April we went at sea again but now to go north towards home!

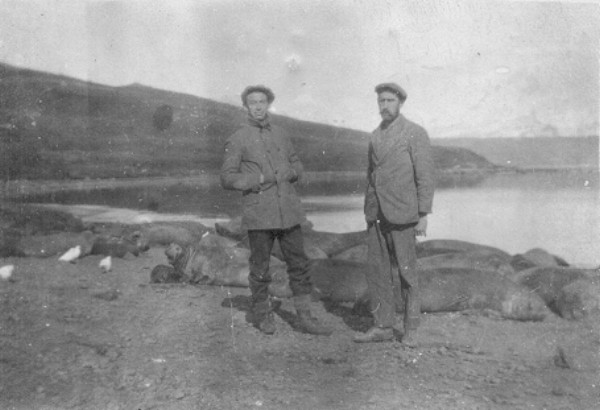

Unknown men at a spot titled Seal Bay In the beginning we had our course set to the north until we had passed the roaring forties. Then we turned west. The first city we met on the south coast of Africa was East London. We stayed for a little more than 24 hours to bunker coal and food. Then we continued around Cape Agulhas and Cape of Good Hope and one afternoon we entered the harbour of Cape Town in very strong winds.

We anticipated that all troubles should be over by now but we were wrong. When all the four ships were gathered it started. Our contract stated: Free return home by a ship decided by the shipping company. We considered that ship meant passenger ship but the company had a different opinion. The two tankers that had been on the island were quickly restored and a tank in their fore peak on each of them was prepared with 15 'hang beds'. But we were 62 in the crew that needed beds. One day the leader of the expedition came to us and said that we sail tomorrow so please take your belongings and embark. But no one took notice of the order. We got further reminders but nothing changed. One day we an ultimatum: 'Go aboard today, Tuesday, or we send the police to pick you up on tomorrow!' We went to our respective consulates, the Norwegian and the Swedish, but they told us that the way the contract was written they could not do anything. But we are not a heard of cattles we said. Sorry, but you have signed the contract and we cannot do anything so you must obey your boss. We will not embark voluntarily, we said, and we live in a civilized society. It is against the law to handle people worse than animals! Our consuls told us to go aboard because they could be of any help. Deep inside ourselves we doubted that the company should call for police assistance and probably that way the arresting went so quick as it did. Early Wednesday morning we went up to the city. A couple of us went to our often used caf named Frascati. We did not see or hear anything from our fellows so before noon some of my friends decided to check the environment. We are soon back they said but the never came back. At noon I was alone in the caf. Then I got restless and decided to go out. The city was empty of my friends and even policemen. Then I went towards the docks. On Dock road there was a caf named Queens Bar. The Bar had two entrances, a small one on Dock Road and the main one from the corner. When I was close to the entrance from Dock Road two policemen came out from the main one with two men each. Now the Bar must be emptied of policemen I thought and went in. I opened the door and entered going backwards in order to check the two policemen just leaving. Just after closing the door I felt a hand on my shoulder and a voice saying: 'here is one more!'. All I could do was to accept my destiny and shortly after I was pushed into a cell where all my friends already were gathered. A few came after me and one did not come at all. His name was Njd, satisfied so I guess he felt satisfied as well.

Later that evening the cell door was opened and one at a time was taken away. No one came back and finally it was my turn to leave. I was brought to a room where I found the Chief of Police, our boss, a secretary and 4-5 policemen sitting. Do you speak English? said the Police Chief. No, I said. A translator was available and through him the Chief started to talk to me in a very gentle and caring tone and finally he said: Now you sign this document and tomorrow you embark the Kildalkey and then all is forgotten. No, I said, I dont sign anything. Maybe my voice was a little lauder than necessary. The Chief also changed his tone. His gentle voice was gone and he became red and blue in his face when he shouted: Sign immediately otherwise you get 3 months in the mountains with Negroes and outlaws cutting stones. For your information, all the others have already signed. Out he shouted and I was taken to an new cell where all my crew mates already were except for one who the Chief managed to convince and frighten.

At midnight we were taken out of the cell, two by two, and linked together two by two. When all were chained we marched away. Outside we were met by soldiers with loaded guns with bayonets. We had quickly become dangerous people. We marched to a police boat that took us to our two ships, anchored in the bay. Early next morning we took off from Cape Town.

Already the first day we lost sight of Kilfenara and we did not spot her during the rest of the voyage. We were sleeping everywhere, in life boats and on deck. As soon as the Captain had had his morning procedures he came to us asking that we should sign the ship documents but he got no name in spite of threatening and begging. We are shanghaied we said, we do not have to sign. The 1st mate came and wanted us to start working but we did not do any work at all. Days become boring doing nothing but we preferred that than making the officers happy.

It took us 30 days to reach Las Palmas where we even this time should take bunker. We had not been there long before trouble started again. Some of the boys had purchased whiskey and rum and when the liquor started to influence them they went to the 1st mate and asked for being transported ashore. The mate refused and than he got a punch on his nose sending him into a corner. He seemed to have been deadly frightened because he ran up to the bridge and hoisted some signals. We could not read the signals but later on we learned: Mutiny onboard, send help. A Spanish marine ship was in the harbour and from them soon arrived two boats loaded with soldiers. They pushed us towards the stern, using their bayonets, into a compact mass and we learned that any type of aggression and they should open fire. The state of siege lasted not so long maybe an hour or less but we agreed upon that we should contact our embassies again and as the ship wore an English flag we even contacted the English embassy. All three, Swedish, Norwegian and English, came aboard and got informed about the circumstances. Already after a few hours we got the information that we should leave Kildalkey in Las Palmas.

'This night or tomorrow a passenger ship is arriving on its way to England. You may go aboard and continue your trip'. This news was accepted with joy and satisfaction but we did not believe that it was true. It is probably a bluff to calm us down and then they take off during the night, we thought. Therefore we had a man at watch in the boiler room the whole night. Any engineer that tried to produce steam should be aware of the situation.

At sunrise the passenger ship arrived and some time later a boat came and took us over to the ship.

But rumour was there before us. When the pilot came aboard the passenger ship he pointed at Kildalkey and said: There you see a pirate ship, full of crazy Scandinavians and they should travel with us. Some old ladies panicked and wanted to leave the ship immediately, but the officers calmed them down and assured that there was no risk at all. Our fellow passengers avoided us the first couple of days but they soon changed their attitude towards us. We had a very nice trip to Liverpool enjoying music, dancing, good food and wines every night.

From Liverpool we took a train to Hull and then a ship to Bergen in Norway. The train trip to Kristiania was an experience I will never forget. In Bergen weather was like summer, but in the mountains there was a snowstorm and minus 20 C. We almost froze to death. We were dressed for sunshine and warmth. I counted 157 tunnels but than I gave up. From that altitude a passenger ship in a fjord seemed big as a fly.

The trip took 24 hours and on the 3 of June 1921 I was back in Tnsberg after 11 months absence. My first trip to Kerguelen was finished.

|

At the time we were on Kerguelen catching seals we normally were on the east- and south coast of the island. It is situated just south of the roaring forties and is frequently affected by storm and bad weather. Days free from storm are few. Wind direction is normally west or north west and they are not summer breezes.

Under this circumstances it is obvious why we preferred to stay on the east or south side of the island to use the lee that the island gave us.

But on one occasion there were two of the ships that took off south hoping to be fortunate on the west side of the island. On one of the ships, S/S Plough I was a crew member.

From the base, Jeanne drc we had around 15 hours voyage. Therefore we divided it in two parts. We had no radio giving weather reports so the barometer and some of the crew who could forecast weather were our guidance. Good weather was highly needed we found out afterwards. The whole South Atlantic was infront of us from Cape Horn and with interference. The first day we steamed to a bay on the South coast called the Elephant Bay. A stream or a small river goes out in its southern part and there was basically the only place to anchor. The waves were rough in the whole bay but we could row a bit upstream in strong current. We arrived in the afternoon and shot some seals before dark. They became a good ballast the next day. Early, at 03,00, we went south to pass the most southern part of the peninsula. The morning was unusually beautiful. When we had passed the cape we met rough sea but the wind was light. Now we came to an area where map had low reliability if not misguiding but our captain had some previous experience of the area. The rough sea helped because you could see from a distance where the depth was inadequate.

Even on the west coast the island is very rocky and there is a large archipelago. Soon we could into this having a smoother ride. We went slowly and used the lead line frequently. Already after an hour or so the look-out told that he spotted seals. Now, we quickly organized our equipment, sharpened our tools and dressed for going ashore. At a fair distance we let the anchor and put the life boat into the water. The boat was fairly big, almost 30 feet and ten feet wide. We could use four pair of oars and sit on thwart each. We rowed a lot, some days maybe 10 km and even more so we had become a good team. We were rowing almost every day. Ashore we took the seals that the look-out had sighted and when the fat was on board it was evening the first day. The day had been successful we all agreed.

We always had a watchman and at 02.00 we were all called on deck. Deepest in the bay there was an glacier reaching the waterfront and getting low tide all ice that had come loose from the glacier followed. The Captain was afraid get fenced in by the ice so he decided we should leave for open water. The ice was already well packed so we had a hard time to get out of its grip. Even next day we had a good hunt and the following night we could sleep without any interruptions.

In the morning of the third day barometer started to drop and the Captain told us that we had to go east again. However, there were a bunch of seals that wanted to take aboard first. We believed that we had plenty of time to board the fat but the margins were small. It was quite common that the barometer drop after the bad weather had arrived and so even this time. We had finished work in land and started to row when the storm hit us. As I mentioned earlier we could handle the oars, both beautifully and effectively. When we were rowing on parade which we did having plenty of time you could only hear one distinct sound in the oar locks when the oars left the water or again went back to the water. Now we really had to ROW. The oars and our backs were bent like bows. When the wind eased a little between peaks we could advance a little but at full strength we almost stopped in spite of using all strength we had. We needed almost half an hour to proceed 200 meters. The last 20-25 meters we were hauled in. A man threw a line and we were hauled alongside. We were totally exhausted.

S/S Plough used two anchors and engine running to stay so we managed to hoist the anchors and found a place with better lee awaiting the storm to ease. It took three days before we could leave. We made no more trip to the west coast. There was plenty of seals but the risks were too big to be stranded and then lost time ate all profit we could achieve.

We were all happy when we rounded the south cape and we reached calmer water again. The other ship had gone further north and had made a good catch but they had been stopped several days because of the bad weather so even their profit was reduced.

|

In a Swedish newspaper you could on read 4 of April 1950 under the headline Did you know that penguins carry their eggs for 7 weeks. This is a truth that can be discussed. We know what is truth in New York can be a lie in Paris.

The truth is that on the South Pole penguins may carry their eggs but further north where it is warmer they have a nest, I know for sure.

During my stay on the island of Kerguelen we used to pick eggs from the penguins nest in order to feed ourselves. On the island the penguins had nests which were taken in use every year. We knew therefore where to pick our eggs when time was right.

One of these places was a flatland at least 500 m long having one nest after the other so close that you could hardly walk in between. There were penguins in great masses, several thousands without exaggeration. There was a chatter and noise that one cannot believe when we intruders came, but no bird moved away from their eggs. One of us lifted the brooding bird and another took an egg or two if the nest contained several. Then we put the bird back on its nest. On one occasion we had a basket, volume approx. 100 litres, that was filled to a third. How many eggs there were I do not know but I guess 30-50.

The eggs were big, like a clenched fist, so we ate only one egg at the time. During a certain time, though, we had eggs for breakfast, lunch, dinner and evening. The eggs gave a nice change in our dull diet.

It was very interesting to study the penguins. Their proper element was the water in spite of the fact that they are called birds. They could jump a meter above the water level, probably during playing. They lived in great colonies at 300-400 animals. Within each group they seemed to have a kind of a guarding system, sometimes even a patrol duty or equal. Sometimes you could see penguins coming to the nest area obviously bringing information of some kind. It is no doubt about that.

If you walked slowly making no other movements you could walk in the middle of a group of penguins. They showed no fear but you could see that you were strongly observed. A small unexpected movement deviant from the normal and they reacted like a lightning. Not only the nearest but the whole group. If you tried grab one by their wing he hit you immediately with a force that created a long lasting wound on e.g. back of your hand.

We saw three kinds of penguins. One approx. 40 cm tall, another 70 cm and a third one maybe 100 cm tall. The middle size was our egg producer. Those were the most existing, the tall ones we could only see as a couple or two. We never noticed that the different species mixed with each other.

Birdlife on the island was very rich. You could see birds like the albatross, measuring more than 3 meters of wing span, to a trout like bird with 15 cm of wing span. The trout family was well represented but also other species, even mainland birds. One of them was very much like a craw but much bigger. Going into the island and close to their nests they attacked unless you had a stick or equal to protect yourself. On the other hand they normally attacked one or two at the time so you were able to defend yourself. There were plenty of other birds and they had one thing in common, they ate seal fat. A one ton heap of fat could be eaten in one hour.

|

The coasts of Kerguelen is very broken with deep fjords, islands and rocky islets. All this makes an archipelago similar to those outside Stockholm and the Swedish Westcoast. Of course, in this archipelago there are several natural harbours, well protected from both storms and waves. On of these harbours is the one of Table Bay. It is called so because of a mountain in the neighbourhood. It is a separate almost regular elliptic formation with vertical walls, at some places even stretching outside of its own foot. The elevation is roughly 100 meters. We were some of the crew that tried to climb the walls but with no success. It looked to be quite flat on top so we named it Table Mountain.

With a starting point in Table Bay the crew onboard S/S Plough had sounded and marked a road through an area consisting of a lot of stones, small and large, visible and submerged, at hide tide hidden by a couple of meters of water. At one spot it was so narrow that you could jump ashore one on each side at the same time. This passage saved us a couple of hours of voyage each time we should go south of the Table Bay area. The knowledge of the passage was kept a secret onboard. None on the other ship knew about our small mapping work. We were great rivals and no one ever told where they had got their fat, especially if they had got a full load in short time. In that case it was a higher secret.

On the different islands in this archipelago there were plenty of seals. At one occasion which I will tell about, we cheated another captain and his crew. It created a big disorder but was solved in a big laughter.

One evening heading for Table Bay for the night we saw one of the other ships, S/S Kildalkey with a crew twice as big as ours. Onboard S/S Plough we were 16 men. When we had got supper and tided us up a little a couple of the crew of Kildalkey including the Captain came onboard for a social visit. It was always nice to have a break from the usual life if we met out in the hunting area. We discussed seals and there living places both in the bow and in the stern. During the talks we understood that they should go to the same place as us in the morning because a big herd of seal had been sighted earlier. This herd was where our passage ended before open water. We will keep an eye of you so you dont sneak away too early was the last they said before they left us that evening. Kildalkey was a couple of knots faster than Plough so leave them behind was mot possible.

Our Captain told the watchman that when you see Kildalkey start hoisting their anchor you call upon us. We leave as soon as we get dressed. Breakfast we can eat on the way. At 04.00 the crew started to move on Kildalkey and soon the capstan started to hoist the anchor. Then we were called upon and when Kildalkey started to move our anchor chain started to come aboard slowly.

When we reached the entrance to our passage Kildalkey was already disappeared round the corner. We had 2 1/2 hours limit and the passage should take one hour. It meant that we had more than an hour before Kildalkey should show up on the scene.

We anchored, went ashore and had shot most of the seals when Kildalkey arrived. To start with it looked like that the Captain of Kildalkey had decided to disappear again when he saw us, because he ordered full astern for a while but than he changed his mind to full ahead instead. Simultaneously they put the life boats into water and before anchoring was finished the boats were coming toward us. The first ashore was the Captain with his Winchester ready and a face red like a turkey. His crew came after, all upset with all possible signs of anger in their faces. They were as I said earlier twice as many as we.

The Captain of Kildalkey shouted: 'Who the hell has promised you to take our seals? We told you yesterday that we were heading for this area'. We were the first and first at the mill mills first our Captain said. By the way, how did you go to come hear, have you carried the ship over the hills continued Kildalkeys Captain. 'It does not matter' our Captain said, 'the main thing is that we were ahead of you'. After some arguing we were presented with an ultimatum: 'If you dont embark and leave the seals behind, we will break all your bones'. After such a threat we found it wise to slowly withdraw but then our Captain found the releasing words: 'Hold it for a while' he said, 'all seals marked Kildalkey, you take care of and then we take the rest'.

Complete quietness lasted for a short while but suddenly somebody started to laugh and soon everyone was laughing. Instead of violence the tense situation was resolved by a liberating laughter. What was said was quite simple but the unreasonable in it was probably what caused the laughter to break out. Humour was the winner.

Our Captain laughed loudly and even Kildalkey's Captain started slowly to smile, wider and wider. He accepted the battle as lost because he and his crew went back to their boats and returned to Kildalkey. A little later they took off and we continued our interrupted work.

|

One of the last days before Christmas 1921 we had entered Greenland Harbour, into the bottom of that fjord. The task was to shoot and interlard a group of seals we had spotted on the beach. Our Ship, S/S Plough, had anchored 200-300 meter from the beach and we, the whole crew except for the Captain, The Engineer and the Steward had gone ashore. To transport the blubber to the ship we used a wire that we brought along. On this wire we should then hook up the blubber, which then could be hauled aboard. The wire was hooked up to the rowing boat that had a line ashore, very loose tied up. The other end of the wire was on board S/S Plough. The weather circumstances on the island were shifting fast. From dead calm to a gale could take 5-10 minutes. That happened even this time. Without warning we had a gale blowing over the island. Ploughs anchor was probably dropped in a slope so when the first wind reached us it pulled Plough, the anchor, the wire and our boat away from the beach. Soon the anchor chain was hanging vertically. 50 fathoms of chain and a heavy anchor was too much for the three persons onboard to haul. They managed a couple of inches in their first attempt. Now they had to manage the ship and the boat first and when the Engineer had got full steam pressure they steamed into more shallow water so the anchor could reach the bottom. After hauling and moving the ship further on they finally succeeded the get the anchor on board. It took them that day and the following night to do so.

We, who were on the beach took care of the bubbler, but after that it was just waiting. We had no food so very soon we got hungry. Later in the evening someone had found some drift wood, the only material on the island that could burn, and made up a fire. Soon everyone was collecting drift wood and it became a huge camp fire. However, the wood was soon used up and when the fire started to die someone found out that fat can burn. Soon the fire became huge again. By chance the fire had been established in a pit in the ground and when the bubbler had melted it filled the pit with fat.

Later in the night we had a fire that was 2 meters in diameter. As we had no food to cook the fire was used as a heat source only. For some time we were sitting around the fire talking but now and then we took a quick walk to improve blood circulation. It became a long night but it ended finally when S/S Plough returned. First thing on board again was to get a huge meal and then a good sleep. On Christmas day we passed the area again and we could see that the fire was still burning.

|

Axel J. Svenson (on right) with his family in Sweden in 1956 Others in the photo l to r Rickard, Tyra, Henning, Ida and Axel Some Family History Brothers: Henning Johansson immigrated to USA in 1908. He became a carpenter and lived in Oakland, California until his death. Rickard Ledelius (Johansson) joined the Swedish Navy in 1908 and became a radio specialist, wireless. He owned a radio shop in Stockholm after retiring. He had one son. Axel J. Svenson b. October 18, 1897, died August 23, 1960. He was a sailor from 1914 until 1925. He married Kathrin in 1925 and worked as a plumber until he got heart problem around 1940. He suffered from a rheumatic fever at an age of 12, resulting in heart disease later on. He had two sons, Gunnar born 1929 and Olle born in 1935, July 9. Sisters: Tyra Johansson never married. Irma Selqvist (Johansson), immigrated to USA in 1918, married a Norwegian carpenter, specialist in parquet floors, lived in Arlington outside Washington. They had two sons and two? daughters. Ida Johansson lived outside Gothenburg, no children. |

|

Olle Svenson |